Long before highways crisscrossed America, rivers served as the original superhighways for indigenous peoples.

Powerful Native American tribes built thriving civilizations along these waterways, mastering river navigation and harnessing the bounty of these life-giving currents.

Their stories remain largely untold in mainstream history books, yet these river-dwelling nations shaped the continent in profound ways that still influence us today.

1. Mighty Mississippians: Masters of the Mound Cities

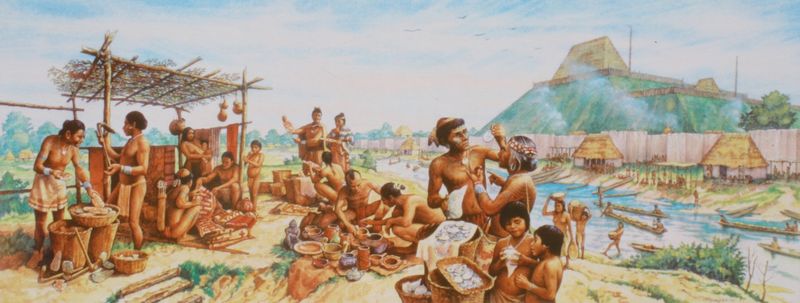

Ancient architects with remarkable vision, the Mississippians transformed river valleys into urban centers between 800-1600 CE. They constructed massive earthen mounds that still stand today, some rivaling the Egyptian pyramids in volume. Their largest city, Cahokia, housed over 20,000 people—larger than London at that time!

These sophisticated societies created extensive trade networks spanning thousands of miles. Shells from the Gulf Coast, copper from the Great Lakes, and obsidian from the Rocky Mountains all flowed through their marketplaces. The Mississippians’ advanced agricultural practices supported their dense populations, cultivating the fertile floodplains with remarkable efficiency.

2. Diplomatic Quapaw: Peacekeepers of the Mississippi

Known as “the downstream people,” the Quapaw controlled the confluence of the Arkansas and Mississippi Rivers—a strategic position they leveraged through skillful diplomacy rather than warfare. Their villages featured distinctive oval-shaped houses built from flexible saplings covered with reed mats, perfectly adapted to the humid riverine environment.

French explorers called them “the most friendly and best-natured of all Indians.” The Quapaw’s agricultural prowess impressed European visitors, who marveled at their bountiful fields of corn, beans, and squash. They maintained peaceful relations with neighboring tribes through elaborate ceremonial exchanges and intermarriage, creating a stable network of alliances that facilitated trade throughout the region.

3. Yuman River Farmers: Desert Oasis Cultivators

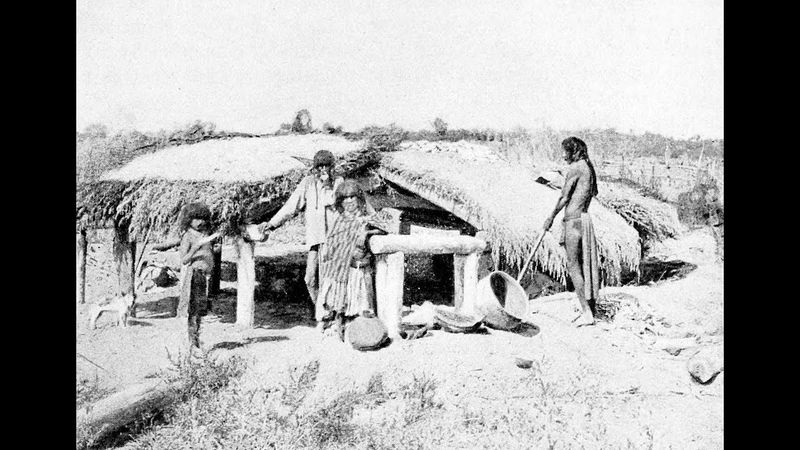

Farming in the desert seems impossible, yet the Mojave and Quechan tribes of the Yuman family transformed the harsh Colorado River region into productive farmland. Their ingenious flood-irrigation techniques took advantage of the river’s annual overflow, creating fertile fields in one of North America’s most unforgiving landscapes.

Standing over six feet tall on average, Yuman warriors were feared for their strength and fighting prowess. Despite limited resources, they developed extensive trade networks stretching from the Pacific Coast to the Pueblo regions.

Their distinctive pottery—created from river clay and decorated with geometric designs—was highly valued throughout the Southwest, with pieces still prized by collectors today.

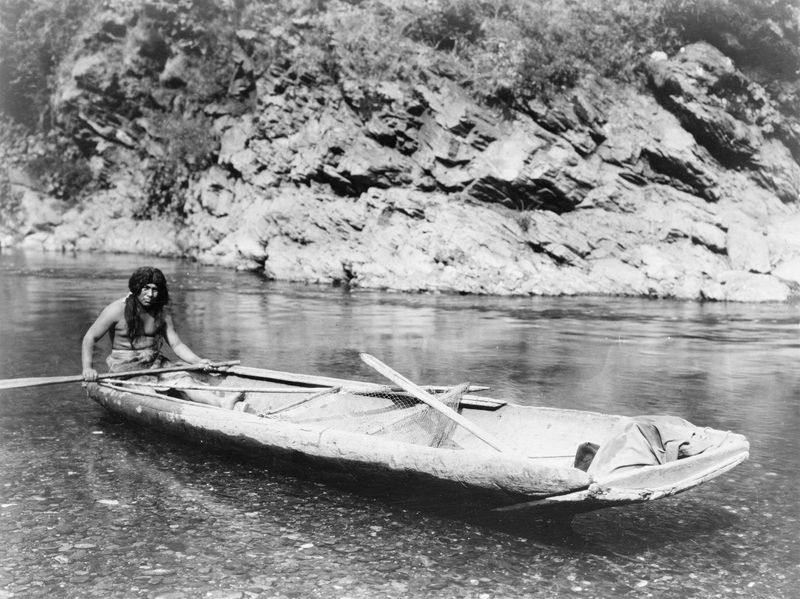

4. Chinook Traders: Pacific Northwest River Merchants

Shrewd negotiators with an eye for quality goods, the Chinook dominated trade along the Columbia River for centuries. Their distinctive cedar canoes—some stretching 50 feet long—could navigate both treacherous river rapids and coastal ocean waters with remarkable stability. These vessels became their trademark, as recognizable in the Northwest as clipper ships were on the high seas.

Salmon formed the backbone of Chinook wealth and spiritual life. Their innovative fishing techniques included elaborate weirs, nets, and specialized spears that maximized harvests without depleting stocks. The Chinook’s trade language, Chinuk Wawa, became so essential for commerce that European fur traders had to learn it to conduct business in the region.

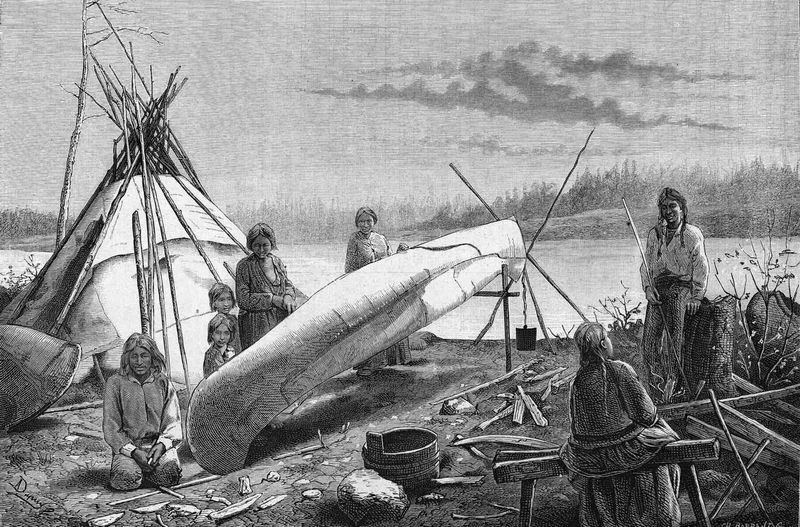

5. Ojibwe Water People: Birchbark Canoe Innovators

“People of the Puckered Moccasin” – the Ojibwe revolutionized northern travel with their birchbark canoes, lightweight vessels that could be carried between waterways yet strong enough to transport heavy loads. These engineering marvels required no nails or metal fasteners, using only natural materials like birch bark, cedar, spruce roots, and pine pitch.

Wild rice—which they called manoomin—formed the cornerstone of their diet and economy. Families harvested this aquatic grain by gently knocking ripe seeds into their canoes with specialized sticks.

The Ojibwe’s intimate knowledge of Great Lakes waterways made them invaluable guides during the fur trade era, though this relationship with Europeans would dramatically transform their traditional way of life.

6. Illinois Confederation: Prairie River Strategists

Controlling the waterway that would later bear their name, the Illinois (or Illiniwek) Confederation united several tribes into a formidable alliance. Their strategic position along this crucial transportation corridor allowed them to become middlemen in the vast trade network linking the Great Lakes to the Mississippi River system.

Buffalo hunting expeditions took them onto the prairies, but their permanent villages clung to river valleys where women cultivated extensive gardens. The arrival of European firearms in the 17th century temporarily boosted their regional power.

Sadly, pressure from eastern tribes armed by colonists, combined with devastating epidemics, caused their population to plummet from over 10,000 to just a few hundred by the late 1700s.

7. Caddo Nation: Southeastern Temple Builders

Architectural pioneers of eastern Texas and western Louisiana, the Caddo constructed some of North America’s earliest permanent temples. Their distinctive grass-thatched houses—shaped like beehives and built around central plazas—created settlements that Spanish explorers mistook for European-style towns from a distance.

Salt production became their economic superpower. The Caddo controlled natural salt springs, processing this precious commodity for trade throughout the Southeast region.

Their sophisticated political system featured hereditary chiefs who governed through consensus rather than absolute power. When French and Spanish explorers first encountered them in the late 1600s, they described the Caddo as “the most civilized among all the nations” of the region—a backhanded compliment revealing European cultural bias.

8. Powhatan Confederacy: Atlantic Coastal Alliance

Forever linked to Pocahontas and early Jamestown, the Powhatan Confederacy was far more complex than portrayed in popular culture. Chief Wahunsenacawh (known to English settlers as “Powhatan”) united over 30 Algonquian-speaking tribes along Virginia’s tidal rivers into a sophisticated political entity controlling nearly 16,000 square miles.

Their agricultural system maximized coastal resources, creating fields by girdling trees to kill them without removing them—a method that prevented erosion while providing natural trellises for climbing plants. Women tended these plots while men hunted and fished.

The Powhatan’s initial strategy of cautious diplomacy with English colonists unraveled as settlement expanded, leading to devastating wars that ultimately destroyed their confederacy by the 1640s.

9. Dakota River Bands: Minnesota Valley Settlers

Before becoming associated with Great Plains horse culture, many Dakota Sioux bands were primarily river-dwelling farmers and fishermen. The name “Dakota” itself means “allies” or “friends,” reflecting their original political organization as a cooperative network of villages along Minnesota’s river valleys.

These eastern Dakota bands harvested wild rice from shallow lakes and cultivated corn on floodplains, supplementing their diet with seasonal bison hunts. Their villages featured distinctive bark lodges during summer months, switching to hide-covered tipis for winter hunting expeditions.

The annual sugar maple harvest brought extended families together each spring to collect sap and process it into maple sugar—a crucial sweetener and preservative in their traditional diet.

10. Natchez Sun Worshippers: Mississippi Mound Aristocrats

Among the most hierarchical societies north of Mexico, the Natchez were ruled by a leader called “The Great Sun” who claimed direct descent from the solar deity. Their complex social system divided people into strict classes: Suns (nobility), Nobles, Honored People, and Commoners—with intermarriage between classes following specific rules to maintain the system.

The Natchez built their principal settlement around a central plaza dominated by a temple mound where an eternal flame burned. Their elaborate burial practices included sacrifices upon the death of elite members.

French colonization in the early 1700s proved catastrophic for the Natchez. After a failed rebellion against French encroachment in 1729, their society was brutally dismantled, with survivors scattered among other tribes.