Before rhinestone cowgirls and pop-country crossovers, a generation of pioneering women laid the foundation for country music as we know it today. These trailblazers broke barriers in a male-dominated industry, bringing authentic voices, innovative sounds, and powerful storytelling to American music. While their names may have faded from mainstream recognition, their musical legacy continues to influence artists across genres to this day.

1. Sara Carter: The Voice That Launched Country Music

From the hills of Virginia emerged Sara Carter, whose haunting alto voice became the cornerstone of The Carter Family’s distinctive sound in the 1920s. As the lead vocalist for country music’s first superstar act, Sara’s emotional delivery on classics like “Wildwood Flower” and “Keep on the Sunny Side” established the template for generations of female vocalists.

Her autoharp accompaniment and masterful interpretation of Appalachian ballads preserved musical traditions while creating something entirely new. Though overshadowed by her cousin Maybelle’s innovative guitar technique, Sara’s vocal contributions were equally revolutionary.

Recording over 300 songs between 1927 and 1941, Sara helped transform rural folk traditions into commercial country music, creating a musical language that still resonates nearly a century later.

2. Patsy Montana: The Yodeling Cowgirl Who Made History

Shattering the glass ceiling with a cowgirl hat and a million-selling record, Patsy Montana rode into music history with her infectious 1935 hit “I Want to Be a Cowboy’s Sweetheart.” Born Ruby Blevins in Arkansas, Montana transformed herself into a western icon during the Great Depression, when female performers rarely achieved commercial success.

Her trademark yodel and upbeat persona offered escapism during America’s darkest economic hours. Montana’s songs painted vivid pictures of freedom on the range—a radical concept for women in the 1930s.

As the first female country artist to sell a million records, she proved women could headline shows and sell tickets just like their male counterparts. Her independent spirit and business savvy created opportunities for every female country artist who followed.

3. Kitty Wells: The Queen Who Answered Back

When Kitty Wells stepped into a Nashville recording studio in 1952, country music would never be the same. Her defiant response song “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels” shot to number one, making Wells the first solo female artist to top the country charts—a revolutionary achievement that shattered industry assumptions about women’s commercial appeal.

The song’s lyrics boldly challenged the double standard that blamed women for failed relationships while excusing men’s behavior. Radio stations initially banned the controversial track, yet it still sold over a million copies.

For the next two decades, Wells dominated country music with her pure, unwavering voice and songs that spoke honestly about domestic life. Her success forced record labels to recognize women as legitimate country stars rather than novelty acts.

4. Minnie Pearl: The Comedic Heart of Country Music

Behind the $1.98 price tag dangling from her straw hat was one of country music’s most sophisticated minds. Sarah Ophelia Colley Cannon created the character of Minnie Pearl, a small-town gossip from fictional Grinder’s Switch, becoming the Grand Ole Opry’s most beloved comedian for over 50 years.

Her signature greeting—”Howdeeee! I’m just so proud to be here!”—masked the classically-trained performer’s genius for social commentary. Pearl’s comedy preserved rural storytelling traditions while gently poking fun at human foibles across class divides.

Though primarily known for comedy, Pearl’s musical performances with country legends helped bridge vaudeville traditions and modern country entertainment. Her character’s warmth and authenticity made her an ambassador for country music during its transition from regional curiosity to national art form.

5. Jean Shepard: The Honky Tonk Pioneer

With her rich contralto voice and no-nonsense attitude, Jean Shepard brought authentic working-class female perspectives to country music during the male-dominated 1950s. Her breakthrough 1953 hit “A Dear John Letter” (with Ferlin Husky) became the first post-World War II country hit by a female artist, capturing the emotional aftermath of wartime relationships.

Unlike many female performers of her era, Shepard refused to soften her hard-country sound for pop crossover appeal. Her signature songs like “Second Fiddle (To An Old Guitar)” spoke directly to women’s experiences in ways few other artists dared.

A founding member of the Grand Ole Opry’s “Grand Ladies” all-female performing group, Shepard’s remarkable 60-year career blazed trails for independent-minded female artists who prioritized musical integrity over commercial compromise.

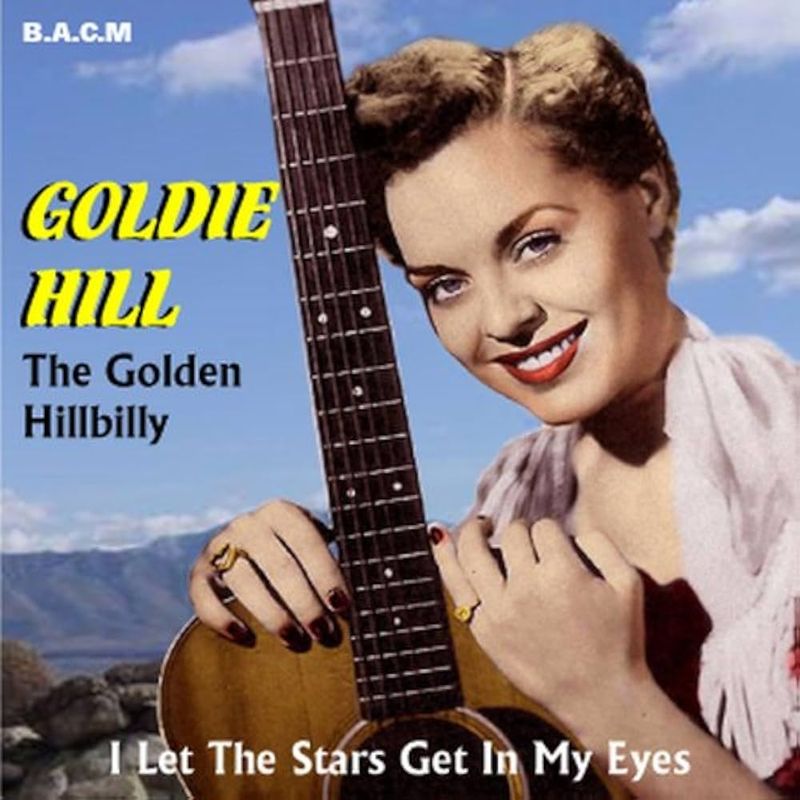

6. Goldie Hill: The Golden Hillbilly

With her striking blonde hair and powerful voice, Goldie Hill burst onto the country scene when female artists were still novelties. Her 1953 chart-topper “I Let the Stars Get in My Eyes” made her only the second woman to reach number one on the country charts, establishing her as Kitty Wells’ most formidable female contemporary.

Nicknamed the “Golden Hillbilly,” Hill’s vocal style blended traditional country with emerging rockabilly energy. Her brother Tommy Hill’s connections as a musician helped open doors, but Goldie’s talent kept them open during a career that produced hits like “Lonely Side of Town” and “I’m the Loneliest Gal in Town.”

After marrying country star Carl Smith in 1957, Hill gradually stepped back from performing. Her brief but significant career demonstrated that country music audiences would embrace female artists with authentic voices and compelling material.

7. The Davis Sisters: Harmony Trailblazers

The ethereal close harmonies of Betty Jack Davis and Skeeter Davis (born Mary Frances Penick) created one of country music’s most distinctive sounds of the early 1950s. Despite not being biological sisters, their perfectly matched voices blended so seamlessly they sounded like one voice split into harmony.

Their 1953 breakthrough hit “I Forgot More Than You’ll Ever Know” topped the country charts for eight weeks, influencing countless vocal groups that followed. Tragically, their meteoric rise was cut short when Betty Jack died in a car accident that also seriously injured Skeeter.

After recovering, Skeeter continued as a solo artist, eventually crossing over to pop success with “The End of the World.” The Davis Sisters’ brief collaboration created a template for close female harmony that echoes through country music history, from the Everly Brothers to the Judds.

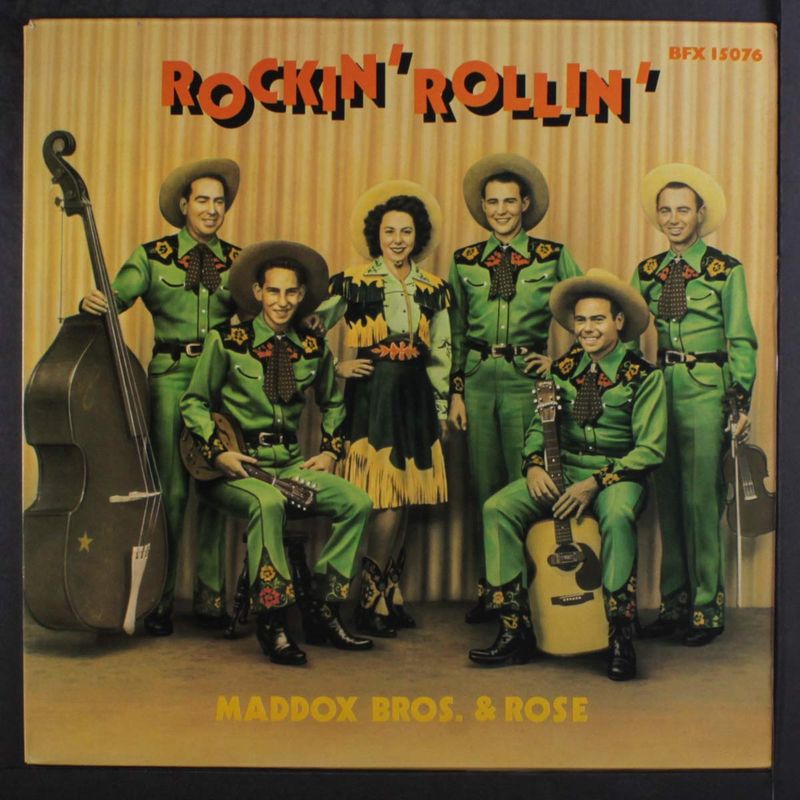

8. Rose Maddox: The Firebrand of Early Country

With her flamboyant rhinestone cowgirl outfits and electrifying stage presence, Rose Maddox fronted The Maddox Brothers and Rose, the self-proclaimed “World’s Most Colorful Hillbilly Band” throughout the 1940s and 50s. Her powerful, unrestrained vocals on songs like “Philadelphia Lawyer” and “Sally Let Your Bangs Hang Down” defied conventions about how women in country music should sound or behave.

Born into poverty in Alabama, Rose and her brothers developed their distinctive sound while working as migrant laborers in California. Their blend of hillbilly boogie, western swing, and proto-rockabilly created a musical bridge between traditional country and early rock and roll.

Rose’s fearless performance style directly influenced female rockabilly artists like Wanda Jackson. After the brothers disbanded in 1956, she continued as a solo artist, later embracing bluegrass and earning a Grammy nomination in her 60s.

9. Wilma Lee Cooper: The Mountain Music Matriarch

Standing barely five feet tall, Wilma Lee Cooper’s powerful, piercing vocals could fill mountain hollows with soul-stirring sound. Alongside husband Stoney Cooper and their group The Clinch Mountain Clan, she preserved Appalachian musical traditions during the 1950s and 60s when commercial country was increasingly smoothing its rough edges.

Born in the West Virginia mountains, Cooper brought authentic gospel and bluegrass sensibilities to the Grand Ole Opry stage. Her unflinching delivery on songs like “The Legend of the Dogwood Tree” and “Walking My Lord Up Calvary’s Hill” earned her the nickname “The Blue Ridge Mountain Girl.”

Unlike many contemporaries who softened their sound for mainstream appeal, Cooper maintained her distinctive mountain style throughout her career. Her commitment to traditional sounds created space for authentic Appalachian voices in country music’s increasingly commercial landscape.

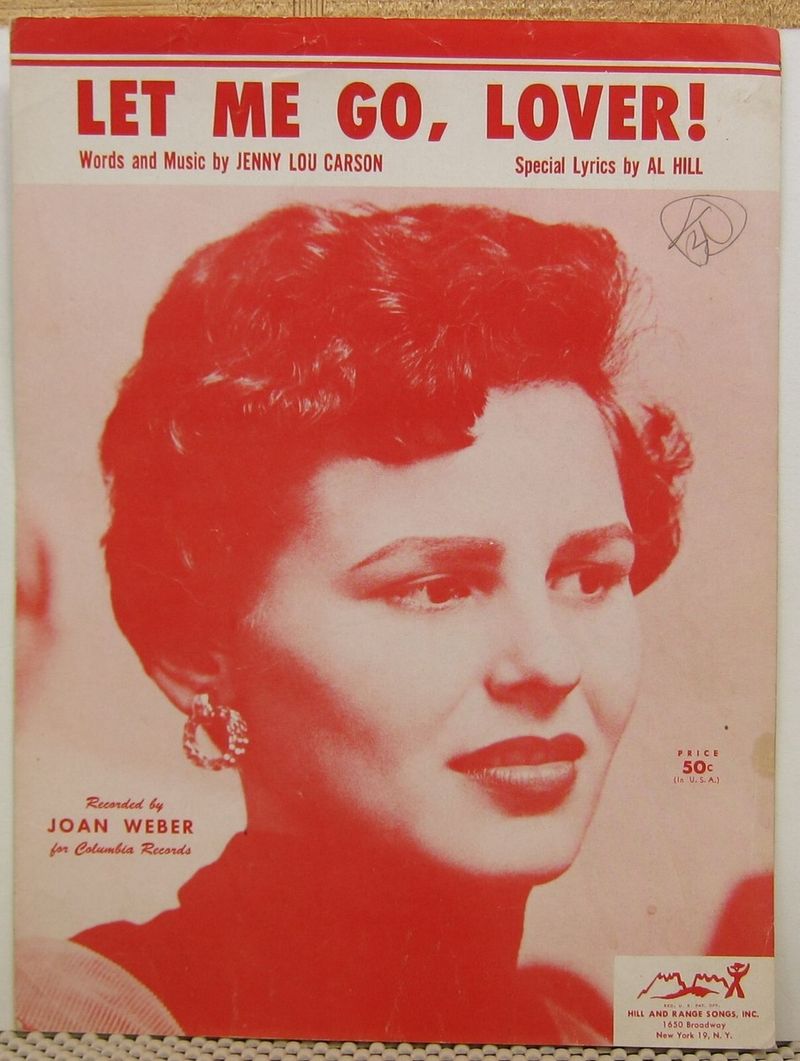

10. Jenny Lou Carson: The First Lady of Songwriting

While male songwriters dominated Nashville’s publishing houses, Jenny Lou Carson quietly built a catalog of hits that changed country music’s landscape. Born Lucille Overstake in 1915, she became country music’s first prominent female songwriter, penning over 170 songs recorded by the genre’s biggest stars.

Carson’s breakthrough came with Ernest Tubb’s 1945 recording of her composition “You Two-Timed Me One Time Too Often,” which spent 18 weeks at number one. Her songwriting explored emotional territory often overlooked in male-written songs, with nuanced perspectives on heartbreak, loneliness, and resilience.

Beyond writing, Carson performed as part of the Three Little Maids and later as a solo artist. A founding member of the Nashville Songwriters Association, her pioneering career opened doors for generations of female songwriters in a notoriously male-dominated field.

11. Molly O’Day: The Voice That Influenced Hank Williams

Few singers could make a gospel song feel like a direct line to heaven quite like Molly O’Day. Born Lois LaVerne Williamson in Pike County, Kentucky, O’Day’s raw, emotionally charged vocals on songs like “Tramp on the Street” and “The Drunken Driver” brought unfiltered Appalachian intensity to country gospel music of the 1940s.

Her husband Lynn Davis’ Cumberland Mountain Folks provided the musical backdrop for O’Day’s soul-stirring performances. Even Hank Williams reportedly admired her authentic delivery, with music historians noting her influence on his gospel recordings.

Despite commercial success and devoted fans, O’Day stepped away from secular music in 1952 to focus on gospel and church performances. Her brief recording career (just five years) produced some of early country music’s most powerful vocal performances, creating a template for the “high lonesome” sound later embraced by bluegrass.

12. Cousin Emmy: The Multi-Instrumental Marvel

Long before women were expected to be anything more than vocalists in country music, Cousin Emmy (born Cynthia May Carver) was mastering over fifteen instruments. This Kentucky-born dynamo could switch from banjo to harmonica to accordion while maintaining her spirited vocal delivery, making her one of early country music’s most versatile performers.

Her 1947 recording of “Ruby Are You Mad at Your Man” showcased her lightning-fast clawhammer banjo technique and distinctive vocal style. Though her stage name and rural persona suggested a simple country character, Emmy was a shrewd businesswoman who carefully crafted her image.

After years on radio and touring rural circuits, Emmy performed at the American Folk Blues Festival in Europe during the 1960s folk revival. Her preservation of Kentucky folk traditions and instrumental prowess challenged gender expectations in country music and influenced the emerging bluegrass genre.

13. Lulu Belle Wiseman: Radio’s Rural Queen

Before television brought entertainment into American living rooms, Lulu Belle Wiseman’s warm, authentic presence made her radio’s reigning queen of country music. Alongside husband Scotty Wiseman on the National Barn Dance radio show, Myrtle Eleanor Cooper (her birth name) reached millions of listeners weekly during the 1930s and 40s.

Known for her gingham dresses and comedic banter, Lulu Belle balanced humor with heartfelt performances on songs like “Have I Told You Lately That I Love You?” Her popularity led to movie roles, political office (in the North Carolina legislature), and a 1936 Radio Guide poll naming her “Radio Queen of America” over established stars like Kate Smith.

The couple’s natural chemistry and relatable personas helped country music transition from local entertainment to national phenomenon. Though less remembered than contemporaries, Lulu Belle’s pioneering career established the template for female country entertainers.

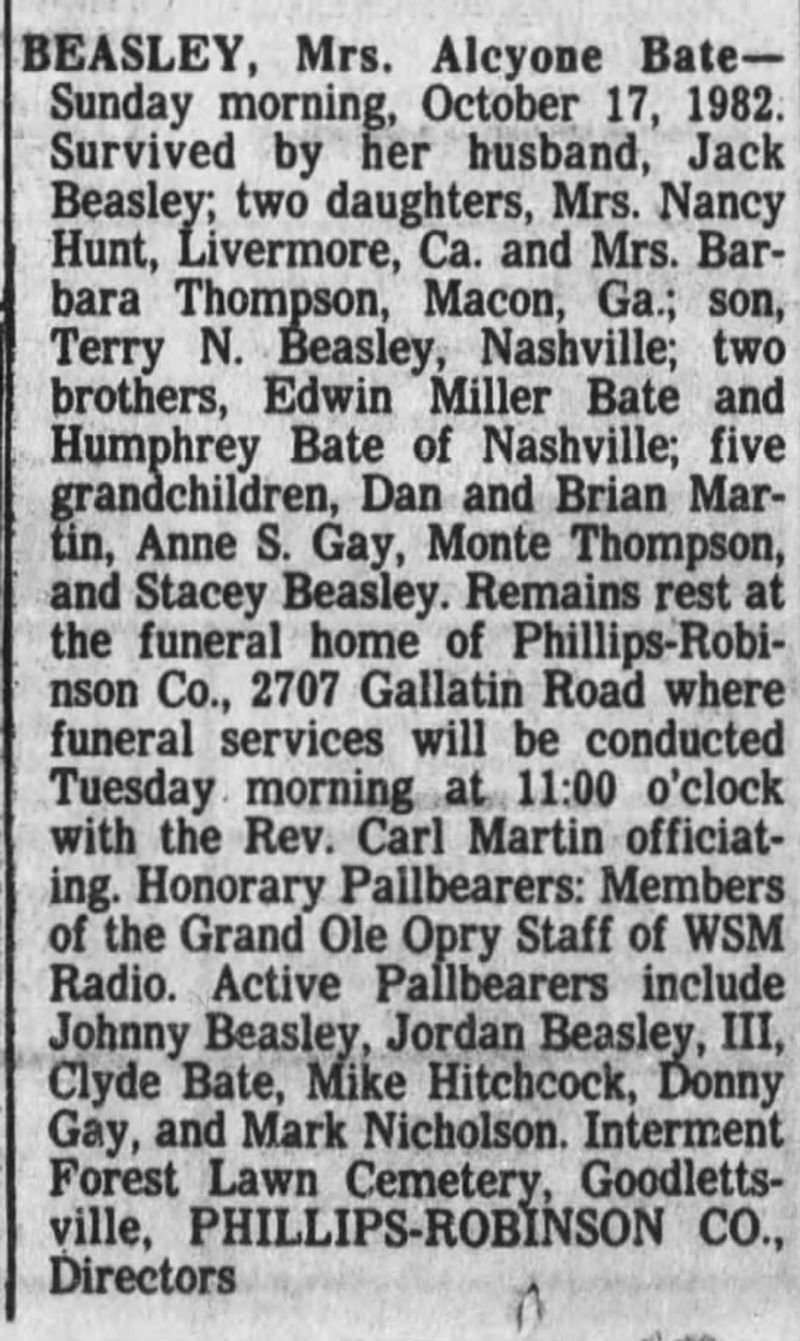

14. Alcyone Bate Beasley: The Original Opry Woman

When the Grand Ole Opry was still called the WSM Barn Dance, Alcyone Bate Beasley was already making history. As the daughter of harmonica player Dr. Humphrey Bate, Alcyone became part of the Opry’s first string band in 1925, playing piano, banjo, and guitar with The Possum Hunters.

Though rarely mentioned in country music histories, Beasley holds the distinction of being the first female performer on what would become country music’s most prestigious stage. Her musical contributions helped shape the Opry’s early sound, blending traditional string band music with gospel harmonies.

After her father’s death in 1936, Alcyone formed her own group, the Bate Quartet. Despite facing gender barriers in the industry, she continued performing into the 1960s, creating a legacy as country music’s original female instrumentalist on a national platform.

15. Patsy Cline: The Honky Tonk Years

Before “Crazy” and crossover fame transformed her into a musical icon, Patsy Cline paid her dues in smoky bars and rural dance halls. These formative years shaped the distinctive vocal style that would eventually make her immortal. Born Virginia Patterson Hensley in Winchester, Virginia, Cline’s early career featured a rawer, bluesier sound than her later polished Nashville productions.

Songs like “A Church, A Courtroom, and Then Goodbye” and “Walkin’ After Midnight” showcased her remarkable ability to convey emotion through subtle vocal techniques. Despite her eventual legendary status, Cline struggled for years in the industry, facing financial hardship and career setbacks.

These challenging early experiences infused her singing with authentic pain and resilience that connected deeply with listeners. Though her life was cut tragically short at 30, Cline’s pre-fame years represent an essential chapter in country music’s development.