When we think about humans, we usually just picture ourselves – Homo sapiens. But our family tree is actually much bushier than most people realize!

For millions of years, Earth was home to many different human species who lived, created tools, and even crossed paths with our ancestors. Some were tall, others tiny, but all were part of our amazing evolutionary story.

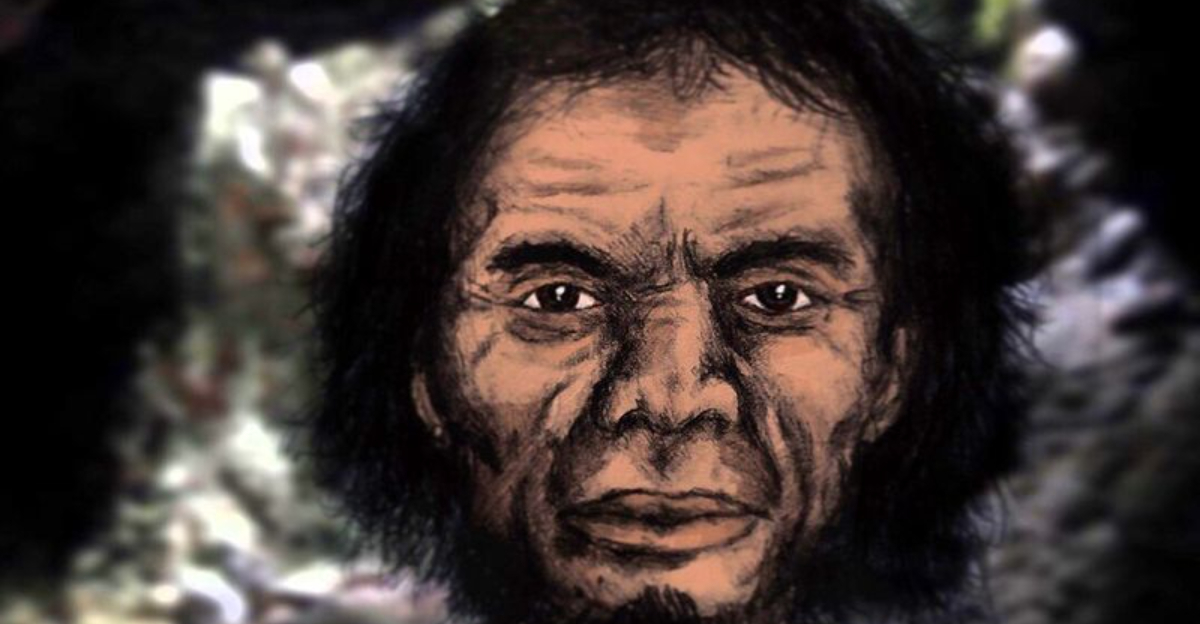

1. Neanderthals: Our Closest Cousins

Stocky, strong, and surprisingly sophisticated, Neanderthals thrived in Ice Age Europe for over 350,000 years. They crafted complex tools, controlled fire, and even created art—challenging our old assumptions about their intelligence.

Their brains were actually larger than ours, though shaped differently. They cared for their injured and buried their dead with flowers, suggesting rich emotional lives.

Perhaps most fascinating, many modern humans carry Neanderthal DNA—proof our ancestors didn’t just meet them, but had children with them before they mysteriously disappeared around 40,000 years ago.

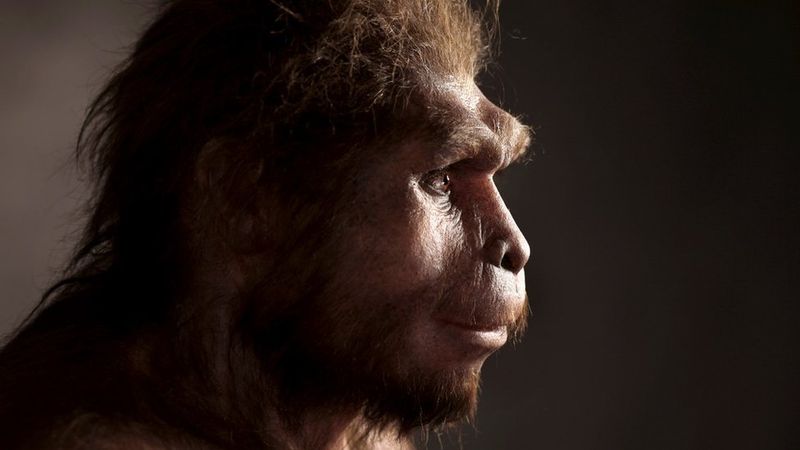

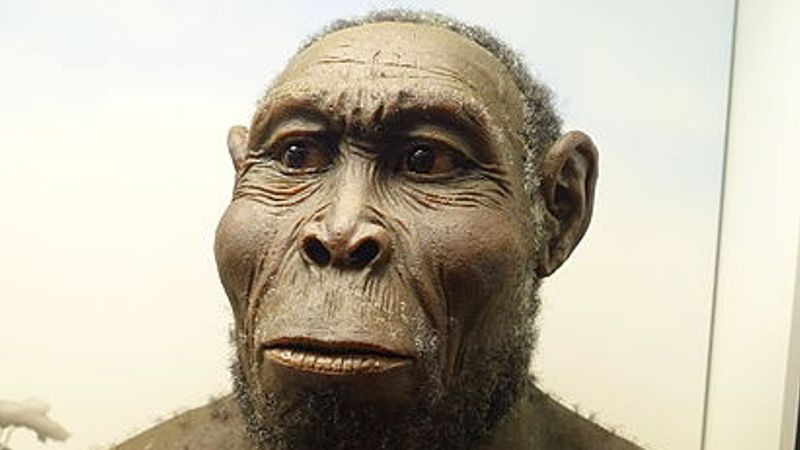

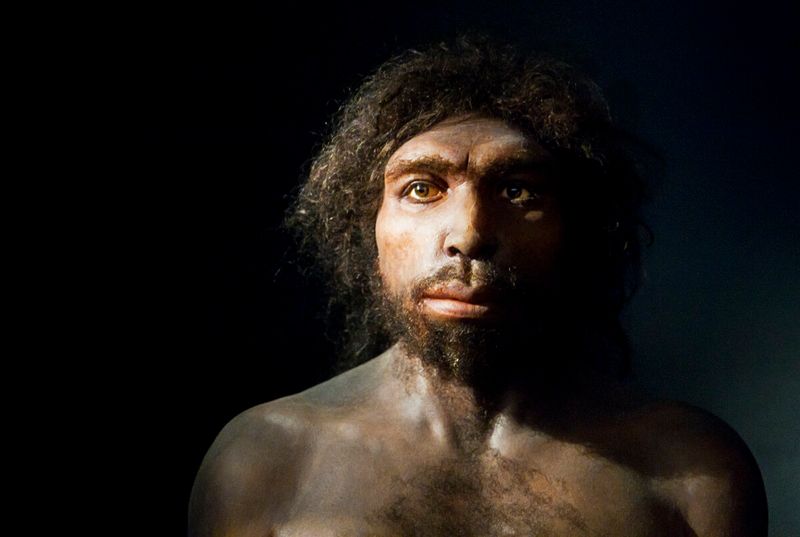

2. Homo erectus: The First Globe-Trotters

Standing tall with a confident stride, Homo erectus earned its name meaning ‘upright man.’ These innovative ancestors were the first humans to truly leave Africa, spreading across Asia and surviving for nearly 2 million years—making them the most successful human species in terms of longevity.

Masters of adaptation, they crafted hand axes and likely invented cooking with fire. Their bodies grew more efficient at walking long distances.

Some scientists believe they even built simple rafts to cross water barriers. Their remarkable journey laid the groundwork for later human migrations, including our own species’ eventual global spread.

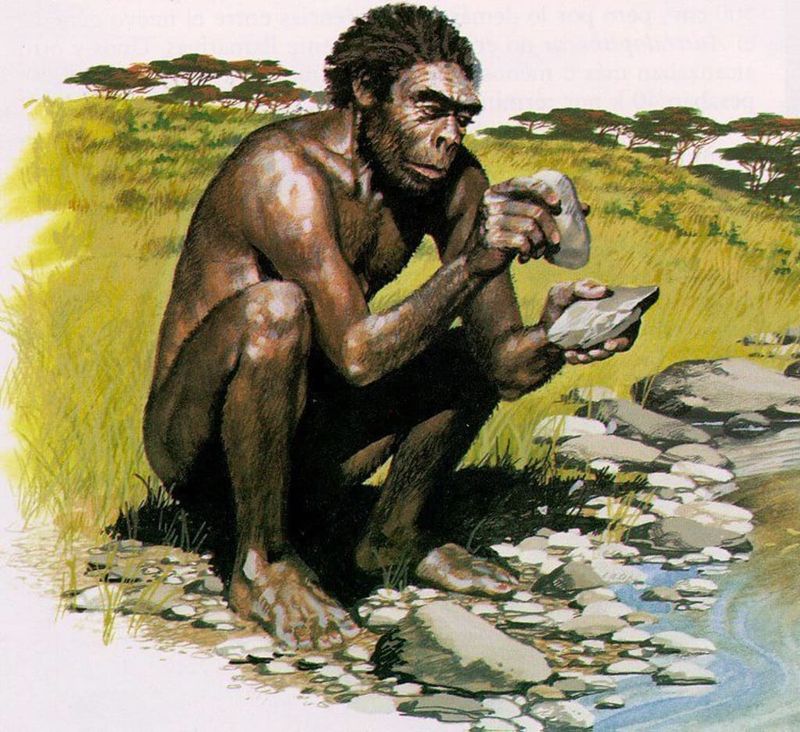

3. Handy Homo habilis: The First Toolmakers

Before smartphones, before writing, before even basic farming—there was Homo habilis, making the first technological revolution. Their name literally means ‘handy man,’ earned by their groundbreaking creation of stone tools 2.4 million years ago.

Living in the woodlands and grasslands of East Africa, these pioneers had slightly larger brains than earlier human relatives. Their fingers were more dexterous too, perfect for crafting simple cutting tools.

While they looked more ape-like than us—with longer arms and a protruding face—these innovative ancestors represent a crucial evolutionary step between earlier australopithecines and later humans like Homo erectus.

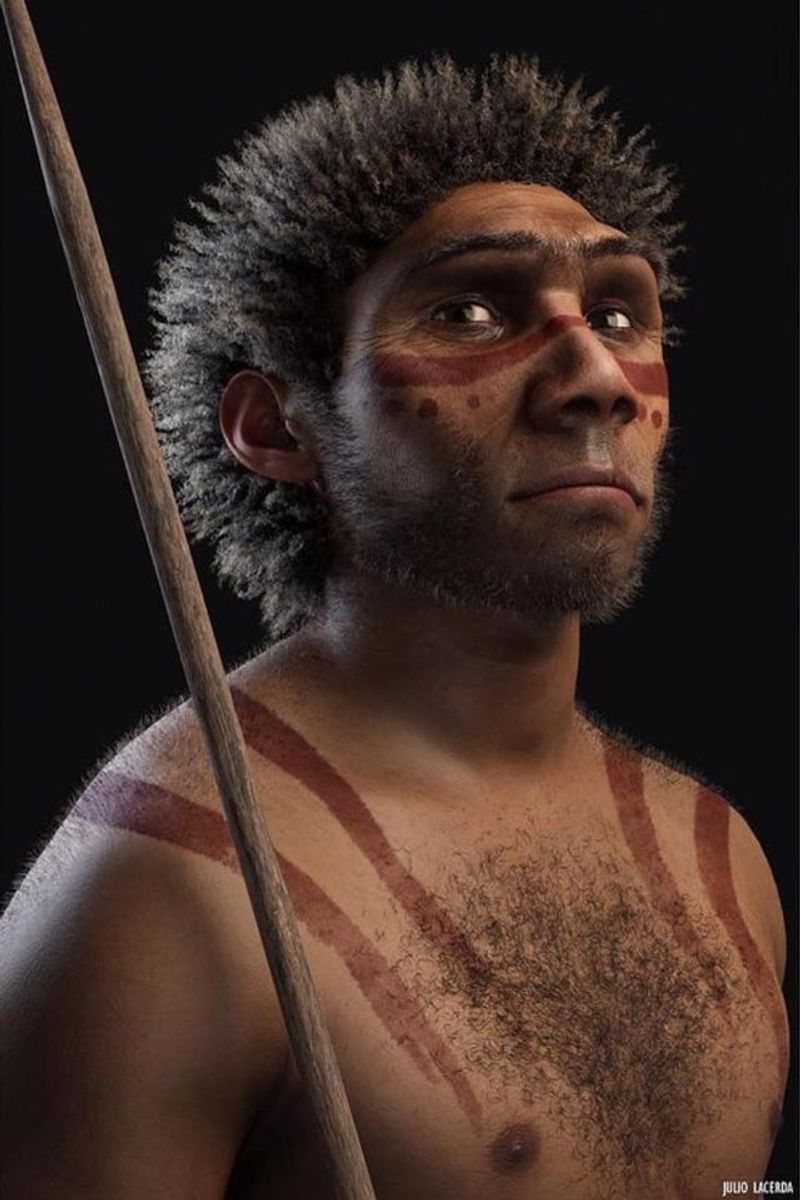

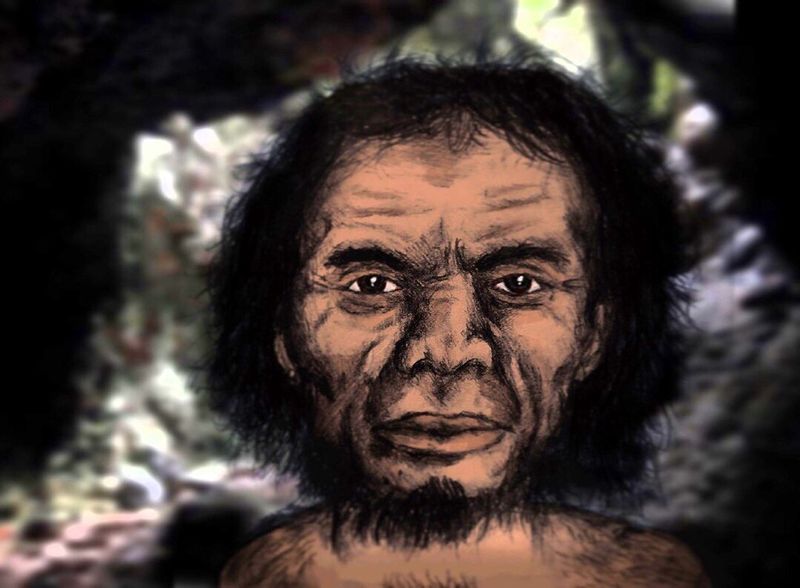

4. Homo heidelbergensis: The Versatile Hunter

Roaming across three continents during the Middle Pleistocene, Homo heidelbergensis represents a crucial evolutionary branch point. These resourceful humans likely gave rise to both Neanderthals in Europe and our own species in Africa.

They hunted impressively large prey using wooden spears—the oldest known throwing weapons in human history. Their brains grew significantly larger than earlier species, approaching modern human size.

Evidence suggests they built simple shelters and possibly controlled fire. Some scientists believe these adaptable humans may have been the first to develop complex spoken language, though this remains speculative based on their throat anatomy.

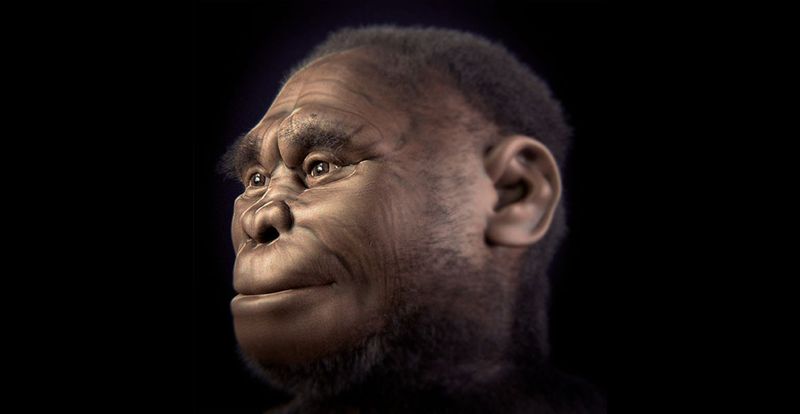

5. The Mysterious ‘Hobbits’ of Flores Island

Imagine stumbling upon a lost world where tiny humans just over three feet tall hunted dwarf elephants! This fairy tale became scientific reality in 2003 when researchers discovered Homo floresiensis on an Indonesian island.

Nicknamed ‘hobbits’ for their small stature, these diminutive humans had brains the size of chimpanzees yet crafted sophisticated stone tools. They thrived in isolation for thousands of years, likely evolving their small size due to limited island resources.

Most astonishingly, they may have survived until just 50,000 years ago—potentially overlapping with modern humans. Local folklore about small, forest-dwelling people has even sparked speculation about whether memories of encounters might persist in cultural stories.

6. Homo luzonensis: The Newest Addition

Discovered in a cave in the Philippines in 2019, Homo luzonensis represents one of our newest family members—and science’s evolving understanding of human evolution. These island-dwelling humans lived approximately 50,000-67,000 years ago, contemporaries of several other human species.

Their fossilized teeth and foot bones reveal a puzzling mix of ancient and modern features. Their curved finger and toe bones suggest they still climbed trees regularly, unlike modern humans.

How did they reach the island of Luzon? Scientists debate whether they had boats or arrived when sea levels were lower. Their discovery reinforces how island environments often produce unique evolutionary paths, creating distinctive human adaptations.

7. Homo naledi: The Cave Stars

Hidden deep within South Africa’s Rising Star cave system lay one of paleoanthropology’s most shocking discoveries. In 2013, explorers found over 1,500 bones representing at least 15 individuals of a previously unknown human species—Homo naledi.

These humans combined a primitive, orange-sized brain with surprisingly modern-looking wrists and feet. Their shoulders were built for climbing, yet their legs designed for walking upright.

Most intriguingly, their location deep within nearly inaccessible cave chambers suggests intentional body disposal—ritual behavior previously thought impossible for small-brained humans. This revolutionary finding suggests complex behaviors might have evolved before large brains, challenging fundamental assumptions about human evolution.

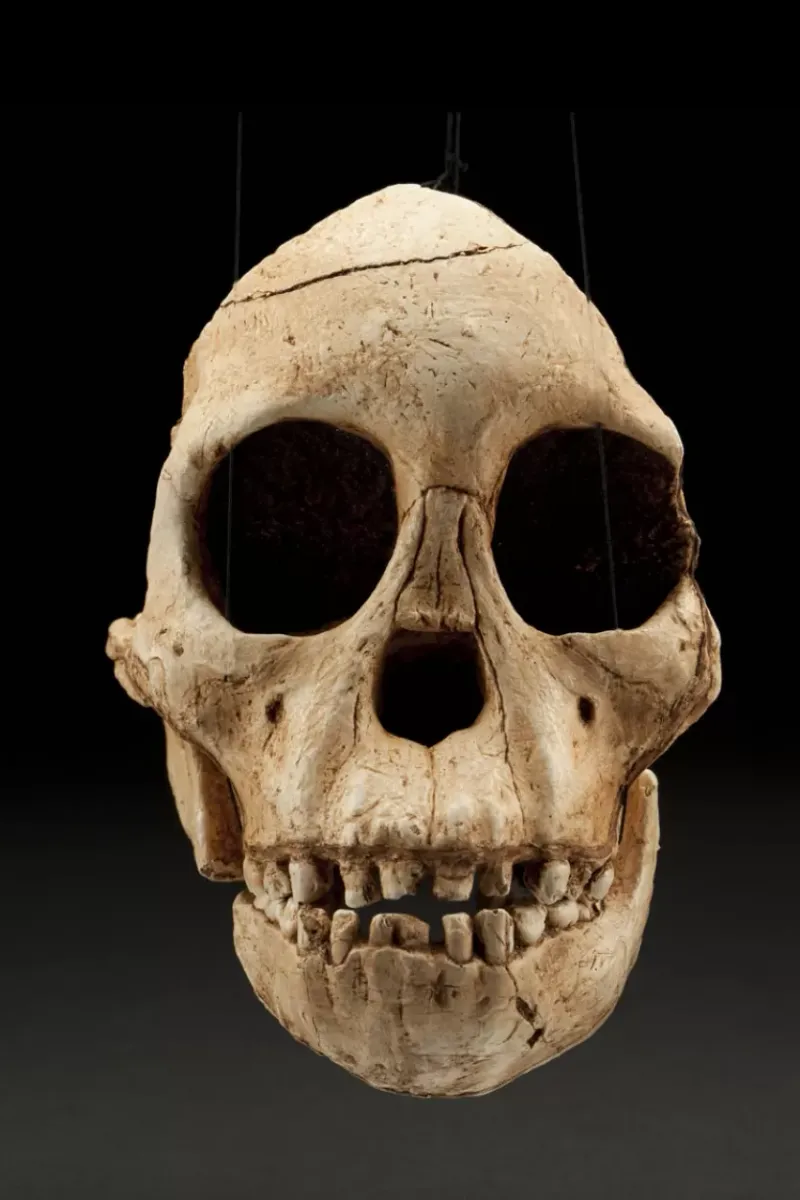

8. Homo rudolfensis: The Disputed Pioneer

Surrounded by scientific controversy since its discovery, Homo rudolfensis represents one of paleoanthropology’s most debated early humans. Known primarily from a single, remarkably complete 1.9 million-year-old skull found near Lake Rudolf (now Lake Turkana) in Kenya.

This enigmatic species combined a surprisingly large brain—larger than contemporary Homo habilis—with a more primitive, flatter face. Some researchers argue these fossils represent normal variation within Homo habilis rather than a separate species.

If truly distinct, rudolfensis likely represents an early experiment in human evolution—one of several contemporary species trying different anatomical approaches to survival in changing African environments. Their story reminds us that evolution isn’t a straight line but a branching bush.

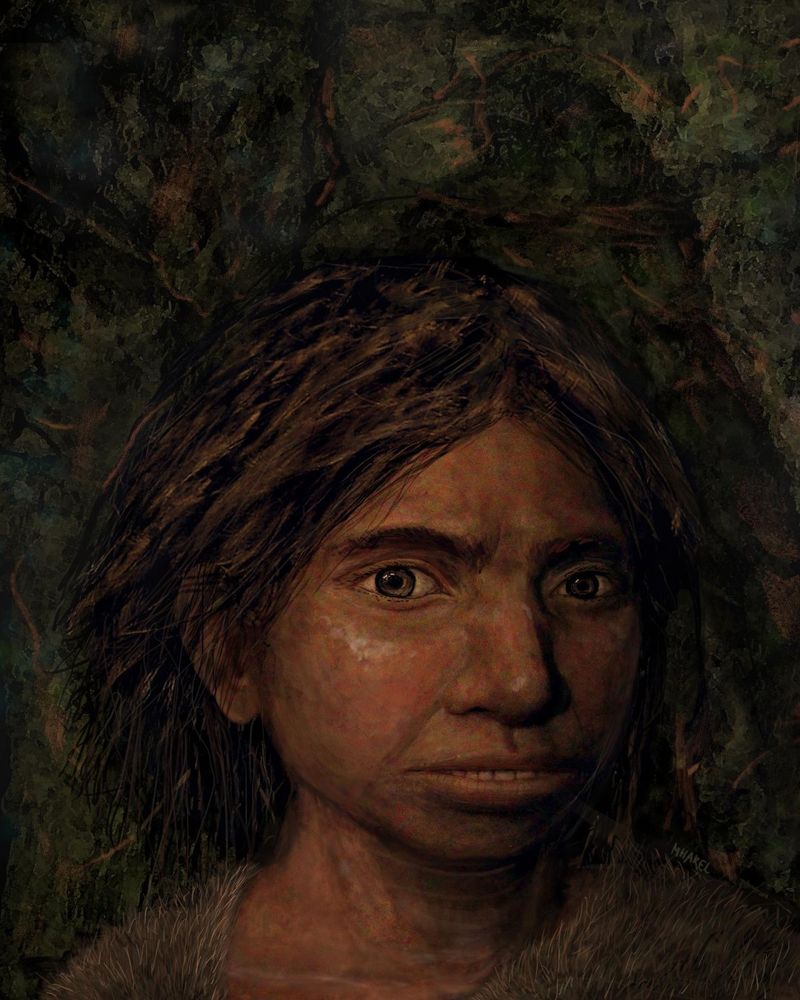

9. Denisovans: Known Almost Entirely From DNA

From just a pinky bone, a few teeth, and a partial jaw, scientists reconstructed an entire human species—the mysterious Denisovans. First identified in 2010 through groundbreaking genetic analysis, these humans inhabited Asia for over 160,000 years.

Though their physical appearance remains largely unknown, their genetic legacy lives on. Modern Tibetans inherited Denisovan genes that help them thrive at high altitudes, while Pacific Islanders received Denisovan DNA that may have aided their immune systems.

Recent discoveries suggest they were robust individuals with wide skulls. The most extraordinary finding? Evidence shows they interbred with both Neanderthals and our ancestors, making them genetic cousins whose DNA we still carry today.

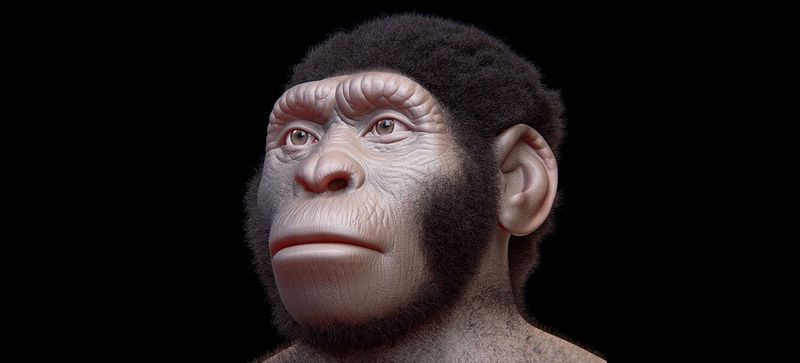

10. Lucy and Her Kind: Australopithecus afarensis

Long before humans crafted tools or controlled fire, a small-bodied, big-hearted ancestor took humanity’s first steps. Australopithecus afarensis—made famous by the 3.2-million-year-old skeleton nicknamed ‘Lucy’—represents one of our earliest walking relatives.

Standing just 3.5 feet tall, these pioneers split their time between trees and ground. Their legs and pelvis had evolved for upright walking, while their arms and curved fingers remained adapted for climbing—the best of both worlds.

Footprints preserved in volcanic ash at Laetoli, Tanzania, provide extraordinary evidence of their bipedal lifestyle. These remarkable impressions show afarensis individuals walking upright across the landscape, leaving tracks virtually indistinguishable from modern human footprints.

11. Australopithecus africanus: South Africa’s Ancient Icon

When anatomist Raymond Dart unwrapped a fossil skull in 1924, he held evidence that would revolutionize our understanding of human origins. The ‘Taung Child’—a young Australopithecus africanus—helped shift scientific focus to Africa as humanity’s birthplace.

Living 3-2 million years ago in what’s now South Africa, these gracile australopithecines had more human-like teeth and slightly larger brains than earlier ancestors. Their curved fingers reveal they still climbed trees regularly, though they walked upright on the ground.

Recent analysis of their inner ear structures suggests they moved differently than we do—possibly with a distinctive head-bobbing gait. Some researchers believe africanus might represent a direct ancestor to the Homo genus, though this remains debated.

12. Nutcracker Man: Paranthropus boisei’s Specialized Diet

Imagine meeting a human relative with a diet so specialized their massive jaw muscles attached to a bony crest running along their skull! Paranthropus boisei—nicknamed ‘Nutcracker Man’—represents evolution’s experiment with extreme specialization.

Living alongside early Homo species in East Africa, these robust australopithecines developed enormous grinding teeth and powerful jaws for processing tough vegetation. Despite their imposing chewing equipment, they stood just 4-4.5 feet tall.

Interestingly, dental analysis suggests they primarily ate grasses and sedges rather than nuts. Their specialized adaptations initially proved successful, allowing them to thrive for over a million years before ultimately going extinct—a reminder that extreme specialization can be both advantageous and risky in changing environments.

13. Homo antecessor: Europe’s First Pioneers

Long before Neanderthals roamed Europe, a mysterious human species braved cold northern climates. Homo antecessor—discovered in Spain’s Gran Dolina cave—represents the earliest confirmed human presence in Western Europe, dating to around 1.2 million years ago.

Their fossils reveal a unique mosaic of features: faces similar to modern humans combined with more primitive brain sizes and tooth structures. Standing about 5.5-6 feet tall, they were accomplished hunters.

Controversially, cut marks on their bones suggest something darker—evidence of cannibalism. Whether ritual or survival-based, this behavior provides a rare glimpse into their social dynamics. Their evolutionary position remains debated, possibly representing an offshoot rather than a direct ancestor of later Europeans.